In September 2019, the Council of Europe (CoE) Committee of Ministers set up an inter-governmental Ad Hoc Committee on Artificial Intelligence (CAHAI). CAHAI is tasked for the next two years to identify potential regulatory frameworks for Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Europe and prepare a feasibility study on these frameworks, with final recommendations to the CoE. ECNL on behalf of the CoE Conference of International NGOs (CINGO) is one of the members of this Committee, and will help coordinate the CSOs’ input. Get in touch if interested to join this important effort!

"There is no question in my mind that artificial intelligence needs to be regulated. The question is how best to approach this.” - Sundar Pichai, Google and Alphabet CEO

Ensuring an appropriate ethical and legal framework for the design, development and use of algorithm-based systems has been the object of a lively debate within national, regional and global institutions in the last few years.

COE and human rights compliance of AI-based systems

The CoE, in particular, has taken several steps towards providing Europe-wide standards and recommendations for responsible development and use of AI. ECNL became actively involved in the process: in early 2019, by becoming observer to the CoE Expert Committee on human rights dimensions of automated data processing and different forms of artificial intelligence (MSI-AUT) In that capacity, ECNL submitted comments and recommendations on the drafting of the Recommendation of the Committee of Ministers to member States on the human rights impacts of algorithmic systems. We also contributed to the drafting of the CoE Commissioner for Human Rights’ Recommendation “Unboxing artificial intelligence: 10 steps to protect human rights”, which outlines guidance to CoE Member States to ensure human rights compliance of AI-based systems. In particular, ECNL provided examples of how automated data processing and AI can be used a) to enhance the meaningful exercise of civic rights and freedoms; and b) to counter the breaches to such rights and freedoms generated by automated data processing and AI themselves.

In September 2019, the CoE Committee of Ministers set up an inter-governmental Ad Hoc Committee on Artificial Intelligence (CAHAI). CAHAI is tasked for the next two years to identify potential regulatory frameworks for AI in Europe and prepare a feasibility study on these frameworks, with final recommendations to the CoE. ECNL was invited to be the official representative at the CAHAI on behalf of the CoE Conference of International NGOs (CINGO). In its role as representative of CINGO, ECNL attended CAHAI’s first plenary meeting in Strasbourg in November 2019 and submitted a detailed response to the first internal consultation launched by the CAHAI Bureau in December. The next plenary meeting is on 11-13 March 2020 on and the first progress report is due by 31 May 2020.

What should AI regulation tackle?

ECNL and CINGO encourage global and regional AI regulation to prioritise the following issues:

1. Unequivocal definition of scope of AI systems subject to regulation

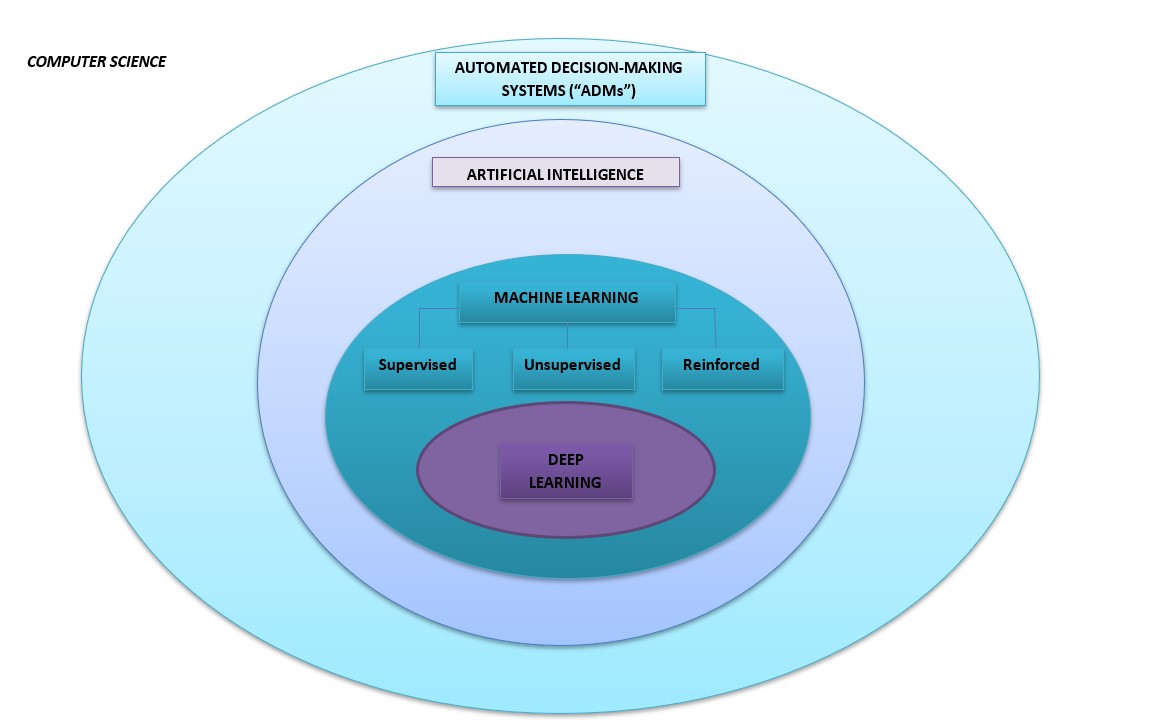

The definition of “AI” is often used to include all algorithm-based systems, that is, not only “machine-learning” based tools - with the ability to identify patterns from large datasets in order to infer further data and constantly improve their decisions without being programmed – but also simple automated-decision-making (“ADM”) tools (i.e., narrowly making decisions based on data inputs). It is important to clarify from the outset the definition and scope of AI analysed by CAHAI and highlight differentiated regulatory approaches to more or less complex algorithm-based systems.

2. Human rights impact assessment of AI-based systems

Any regulatory approach to AI should ensure that AI-based systems are regularly subjected to mandatory human rights impact assessments. In particular, for AI-based systems procured, designed, developed and or/used by public institutions, these assessments should be carried out horizontally across the relevant public policy sectors, i.e. involve all the public policy departments affected by such AI-based systems. These assessments should take place before AI-based systems are publicly procured or designed, during their development and throughout their context-specific use, in order to identify and prevent risks. Bearing in mind that a human rights impact assessment can vary when applied to different AI-based systems and that some AI-based systems may be potentially more harmful than others on society at large or groups of individuals, any chosen regulatory approach should establish:

a.) minimum common criteria and methods to conduct a human rights impact assessment (e.g., Who should be in charge each time? How would the results be accessible and/or contestable?);

b.) benchmarks to identify AI-based applications with potentially high risks to human rights (e.g., How many people would be affected by their decision? What short/medium/long-term consequences would the decision have?) and therefore in need of more complex evaluations.

3. Inclusive participatory approach in regulating and assessing AI

When adopting or amending their specific national regulatory frameworks on AI, states should cooperate and consult with all the relevant stakeholders, including private sector actors, academia, relevant human rights groups and CSOs. Representatives from vulnerable or marginalised groups should also be allowed to provide input. In particular, states should:

a.) establish regular multi-stakeholder consultative mechanisms whenever they review their national strategies on AI and improve communication of such strategies towards the large public;

b.) develop criteria, methods and benchmarks to conduct human rights impact assessments on AI-based systems;

c.) undertake human rights impact assessment before, during and after the design/development/implementation of AI-based systems.

A regulatory framework should also establish minimum criteria for private entities to hold consultations with relevant external stakeholders – including relevant human rights groups and CSOs – at various stages of design, development and use of AI-based systems, in order to facilitate a proper understanding of their intended effect, their way of functioning and their expected impact on an individual, a specific group of people or society at large.

4. Transparency of use and functioning of AI-based systems

Regulatory frameworks should always grant the right of individuals to know when a decision affecting them is made with the assistance of an AI-based system. The information available should include a clear explanation of how the decision has been made, the benchmarks used for the outcome and whenever possible, the right to opt out of being processed by an AI-based system and/or to contest its outcome. Open access to the source code of the AI-based systems should also be included by default in the contracts with companies delivering such systems and could be refused only on the basis of legitimate reasons clearly established by law and ascertained by the public authorities.

5. Traceability/accountability of AI-based systems in use

Regulatory frameworks should include clear transparency benchmarks for the public procurement, design, development and use of AI-based systems. First of all, member states should establish public registers to account for all AI-based systems that are being procured, designed, developed or used by the public sector both a national and local level. Such registers should provide information on the AI-based systems’ scope, way of functioning, the entities responsible for their development, the results of the regular human rights impact assessments conducted as well as the stakeholders involved in such assessments. The obligation to be registered should also be extended to those AI-based systems used by private entities whenever they have been identified as having a significant impact and/or potential risks to the human rights of an individual, a specific group or society at large, based on the benchmarks established for their regular impact assessments. In any case, private/external service providers should submit all information on their systems to the relevant public authorities who will be using or whose work will be affected by such systems. All data included in the registers and their variations should be publicly available and accessible.

6. AI literacy and education

The people need to understand, learn and discuss at least basic consequences of applying algorithmic systems that impact our lives. Therefore, digital education and literacy should step up as an overarching priority for every state and be included in any regulatory approach towards AI research and application. Digital literacy should not only be taught in schools from an early age as an inescapable educational skill but should also be promoted as a “citizens’ skill”, i.e., as a tool that requires lifelong learning across all citizens’ sectors, including vulnerable and marginalised groups.